|

| Giovanni Schneider checks a wool top at the factory of Schneider Group in Biella, Italy |

The drive from Milan to Biella was a fast one that as an Australian I am unaccustomed to. We are doing more than 160 kilometres an hour and in that bandwidth of speed where in my country you instantly lose your license for a year. I am finding it hard to concentrate and recognising this, Giovanni slows down.

I have come to Biella in search of what happened to an Australian bale of wool once it left the farm gate. We Australians see it either as a greasy wool fleece laid on a classing table or as a finished suit. For those of us that are more sartorially inclined perhaps we have seen and touched a bolt of fabric at our tailor’s workshop. But for the vast majority of us, myself included, it seemed shrouded in mystery and often illogical. Why don’t we process wool in Australia? What exactly is it that the Italians do? And why are the Italians still at the height of their game when it comes to making beautiful tailored clothes for men? And so my story starts with Giovanni’s family.

At the beginning of the 20th century his great grandfather was a mechanic who built textile weaving machines for the Marzotto fabric family amongst others. He was a technical specialist. His son, at the conclusion of the first world war had become a pacifist and wanted nothing to do with war or Europe’s problems. But his father did not want him to leave the business and would not fund his move to Australia. So instead, his son, Giovanni, came up with another solution – he took money from the surrounding cloth families and promised to secure them their wool in Australia and promised to sail it back to them in Italy. This was the origins of the G Schneider Wool Group which, today, still owns the majority shares in one of Europe’s last wool processing plants that produces wool tops ready for spinners.

What does this mean for our Australian bale of wool? In its most basic function, the factory is one of three facilities in Europe that can take a bale of wool, open it up, wash it, scour it, blend it, card it and comb it until all the fibres are lined up into lovely slivers of wool that become wool tops that are ready to be sent on to the dye house before being spun into thread. The company was once predominantly a wool sourcing company but in the 1990’s it began to ramp up the processing of wool as many other companies began to wind down their operations concurrently with the rise of China.

Today, about 75% of the world’s wool production goes straight to lower cost producing counties like China. The remaining two processing plants in Italy tend to concentrate on higher grade fibres that tend to go into weaving suit cloths and luxury knits. It is for this reason that the remaining luxury brands such as Brunello Cucinelli, Marzotti, Zegna and Loro Piana all have shares in this facility. Their only local competitor is in a similar ownership, a partnership between Reda and one of the biggest and oldest fabric companies in Europe, Vitale Barberis Canonico.

Vitale Barberis Canonico is one of the oldest companies in Italy with records of transactions dating back to 1663, although many of their detractors say this has been contrived to create lineage. There is a great deal of snobbery in these parts of Italy where lineage and prestige matter. My contact, Giovanni Schneider, great grandson of the original Giovanni Schneider, is on a whatsapp call on my phone speaking in Italian trying to orchestrate a drop off for me on the side of the road at the exit for Biella. There I am to wait for a car before I head to Trivero, in the hills of Biella.

Two African women in unusual short red jump suits are in the car park where I wait. Giovanni tells me they are working girls from Milan who live in these parts to save on money. They appear foreign in this landscape which looks more Switzerland than Italy. A few minutes later I am picked up by Silvio in a sharp window pane check suit in a black BMW station wagon. He hurtles the car towards the base of the mountains ducking and weaving between cars on a two-way road. I am trying to take notes on my phone about the landscape but with each corner I am starting to get queasy. At the base of the mountains we start a windy ascent and I open the window to get fresh country air. The landscape is stunningly beautiful, verdant, somewhat manicured, definitely organised, and with a hint of The Sound Of Music. The buildings are Italian but there is something unusual I can’t quite put my finger on. We arrive in Trivero and the driver stops and tells me to enter through the glass doors. My contact, whom I had met in Sydney for their inaugural Wool Excellence Awards, was a sophisticated man in his early thirties, Simone Umbertino Rosso. However, he had been held up in another part of the country on business and so I was introduced to Valentina Berti, his offsider, who chaperoned me around the facilities.

Vitale Barberis Canonico, receiving their wool tops from their own processing facility, begin dyeing wool tops in large bullet like chambers by robotic machines that retrieve the wool top and plonk it into vats that heat the wool up to 70 degrees, varying temperatures over the course of three hours to ensure the dye penetrates. Once this has been done, the wool tops are sent to the spinners who prepare the fibres and twist and turn them into threads. This is itself another art form in which fibres become like grapes from a vineyard, they can be blended and mixed between varieties (think merino, cotton, mohair, cashmere, silk and linen) and colour, to make different qualities you often see on the inside label of your jacket. This complex process all happens within this enormous facility running over multiple buildings, each comprised of many levels. It uses a mixture of machines, robots and humans to produce over 10 million metres of wool fabric every year. As Valentina explains, if you laid the wool out straight it would reach from Biella to Japan.

As we tour the factory I announce that I have an allergic reaction to sulphur, something which I had as a child. It sends me into shock. Some phone calls are made and I am told we won’t be able to see some of the systems, though I am assured that very few chemicals are employed in the processing of wool. However, a lot of water is used and dye, and in the past, much of this was just sent down river. Today, Vitale Barberis Canonico has a large and extensive water treatment centre adjacent to the factory and there is a big pond of thriving coy fish at the end of this process to assure visitors that they are running a sustainable and environmentally friendly factory, despite the numbers that are being produced inside. And it’s needed. Those millions of metres of fabrics require more than 60 litres per metre to produce from start to finish from the washing of the wool to its finishing treatments. The water required explains in part why Biella became a hub of wool textiles. It has plentiful access to high quality soft water which is perpetually melting from snow on the Italian Alps. Its called soft water because of the lack of mineral content which is in part owing to the types of rocks the water cascades over as it falls. If Biella was an Australian town it might be best described as Tumbarumba or Batlow – at the foot hills of mountains, close to snowy Alps that bring a consistent water supply of ideal quality water.

Back inside the factory I am told I cannot take unapproved photos. The company likes to keep the names of the manufacturers of their machines to themselves along with their robotic processes and some of their weaving methods. It is understandable, Biella was once home to 500,000 people . That population has dropped by 150,000 in the last twenty years. Businesses are boarded up, other companies have moved offshore. In order to stay alive VBC and others have had to increasingly on machines and automation and less on human input. Though they pride themselves on inspecting all cloth with their own eyes at every stage, over time it is foreseeable that those eyes might be digital.

Inside the design room I meet Michele Papouzzo, head of the cloth design team. He and his offsiders Stefano and Andreas are impeccably dressed for a room that is over 100 kilometres from Milan and with very little around it. Michele is dressed in navy melange pants, belt, white shirt, double four in hand knotted tie on an sky blue Garza weave. Stefano is in a French navy suit with Bengal striped shirt and silk grenadine tie. Andreas is in an unusual spotted weave wool suit with Oxford weave shirt, spread collar and floral tie. This is Italy, of course. I ask questions and we exchange ideas about wool. I am told that I have many misconceptions about weaving looms. They explain to me that the types of designs you can weave in wool are much less complex than those of a jacquard loom for silk. More importantly, most of those ten million metres are done in simple dark blues and greys varying in weaves and weights. The market for more vibrant wools is minimal and the mustard yellow wool I photograph is very rare indeed.

Before I am picked up by Giovanni for lunch I am seated on a soft chocolate brown leather sofa and explained the process of wool again. I am reminded of something that I once heard which I later see first-hand – that when wool is washed initially, the lanolin is extracted from Australian merino. It is then on-sold to the cosmetics industry giving an additional revenue stream from the processing.

As I get up to leave, I am graced with the presence of Francesco Barberis, creative director of VBC. He is has become somewhat of an internet icon – as often menswear bloggers on hunt to unpick a suit and talk about its construction, will often be lead back to the cloth makers such as Vitale Barberis Canonico. He is after all the man behind the many millions of metres that go into the suit you are likely to be wearing from your favourite Italian designer – be it Armani, Versace, Prada, Gucci, Ralph Lauren or your local tailor – chances are your wool came from his factory. I managed to get him for a photograph and we spoke briefly about a common person we both knew. “It’s a shame you are going now. Stop past again if you come in this direction”.

I looked around the room, it had, well, a 'hint of fascism' look about it. Perhaps it was the inter-war period model cars that were on the side board or the way the factory was nestled into the mountains like some sort of heavy water treatment facility. I did not know exactly why, but it didn’t feel like I would be ever able to drop in unannounced.

|

| Francesco Barberis And Valentina Berti of Vitale Barberis Canonico |

Giovanni Schneider picks me up and we ascend the mountain further, dropping in on his maternal great grandfather’s house, Casa Zegna. Ermenigildo Zegna is legendary in these parts. He was one of those fastidious types that not only built a business but a town and a culture around the production of both wool and finished garments. His house, which is mostly boarded up, is maintained by a family foundation. A small walk way connected Zegna to his weaving and making factory which ran adjacent and which still operates today in the exact same manner, save for the roof which has been converted to solar power.

Giovanni explains that for the original Zegna it was very much about community, and like aristocrats of the past, he tried to improve the quality of life for all with hospitals, retirement homes, residential buildings, shops and even a mini ski resort at the top of the mountain.

We stopped for lunch at the ski resort. One restaurant was still open. We had cheese and cured meats for anti pasti, gnocchi for pasta, followed by some beef in gravy. As I mopped up the sauce with bread I looked up and saw the timber seemed to be need a sanding back and varnish on the awning. All I see is maintenance expenses and headaches for the descendants of these early pioneers of textiles. Even the forests the early Zegnas planted, the gardens, the roads – all need to be maintained. Only the vista of the Italian and Swiss Alps seems to be free of charge.

It doesn’t help that the Italian authorities now keep a very close eye on all these companies. Based on austerity measures there are far more people working for the tax department and regulatory authorities making it harder and harder for Italians to do business in their own country. It is no wonder that companies like VBC will increasingly try to reduce labour costs in their facilities.

After lunch we go to look at the processing facility of the G Schneider Group. We walk around the offices. One room is sealed off as tax department experts investigate with a fine tooth comb the interactions between the Biella plant and the parent company in Switzerland, just a short drive away. As a foreigner I don’t understand why anyone wouldn’t use the proximity to Switzerland to their advantage, but as Giovanni explains, Italian sentiment has changed. And though the Schneider Group also has factories in Egypt, Mongolia and Iran, it is the Italian factory which gets scrutinised.

|

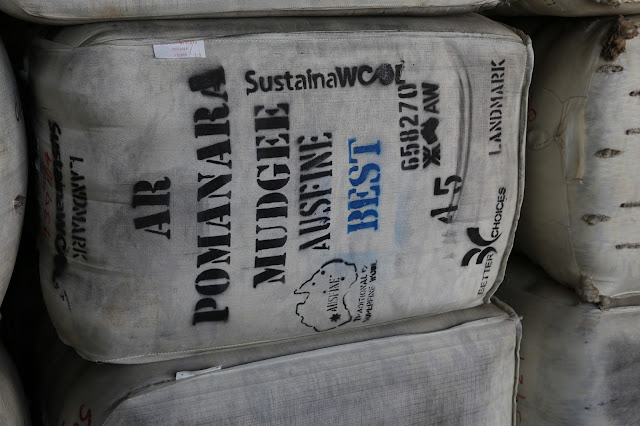

| Australian Bales Of Wool Acclimatising For Processing |

|

| Wool on the factory floor |

As Giovanni opens the factory floor door, I am filled with a sense of alarm like waking up from a bad dream on an aircraft and not being able to get your bearings. There is this mad rush of the Australian countryside, as though I were in the shearing shed with the shearers and wool classers. But no, I am still in Italy. There in front of me are rows upon rows of hyper-compressed wool bales all stacked factory ceiling-high and waiting to be processed. They bear familiar marks like maps of Australia and stencils like “Pomanara Mudgee AusFine” and I am filled with a pride that almost brings a tear to my eye, just like a Qantas commercial. The tightly held together wool bales are opened up using a special machine because if you opened them by hand they could kill someone as they expand. Once the bales are open, the fibres are allowed to sit for a few days to expand and acclimatise. I stick my hand into a mound of wool and am met with that familiar greasy feel from my University days when I drenched sheep in the summer time. I am reminded of the gruelling intensity of work that farmers undertake every year to get those sheep to fill these bales.

|

| Giovanni Schneider |

Giovanni pressed another six digits into another door and we move from the storage facility into the washing room, a bath that looks like something out of Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory takes merino wool and begins washing all of the Australiana out of it, forks dipping and lifting the wool in and out of varying temperatures , the process repeating until it comes out the other side all white and fluffy. The sooty brown water which emerges is siphoned off to another treatment facility that extracts the lanolin into a blue drums.

|

| Bathing and washing wool |

|

| Lanolin extraction of the wool and distillation |

|

| Processing wool |

The wools, now white and fluffy, are sent through a machine which mixes them all together. This ensures that there is a uniform average staple amongst the fibres and to ensure that the spinners have the best possible chance of weaving an even thread. Next the wool is carded and combed, allowing all the fibres to be straightened and aligned and that all vegetable matter is now removed from the original wool fleece. These machines keep running the wool until it begins to look and feel like a lovely mane of hair that has been turned into a kind of rope. It is then cabled into big drums before being compressed into a wool top.

This process is done for wool, mohair, cashmere and for the four million euros worth of vicuna wool that has recently been delivered to the factory floor by air freight for insurance purposes. The factory runs 6 days a week, 24 hours a day.

|

| Vicuna on the factory floor |

|

| South African mohair on the factory floor |

When we leave the main facility I am shown the power plant, a natural gas operated engine room that creates steam and electricity used by the facility. The water, soft from the Italian Alps behind us, is drawn from soft water aquifers beneath the ground. It could be in Australia – it really could, but it took Italians over 100 years to develop this system of processing and it was now processing fibres from all around the world.

That smell of the wool had made be yearn for my own country, for the heat of an Australian summer. I could hear Dorothy Mackellar saying:

I love a sunburnt country, a land of sweeping plains, of ragged mountain ranges, of droughts and flooding rains

We drove back into Milan and contrary to what I had been told, Uber was available. I booked a ride back to Lago Como where I was staying by the lake’s edge. I had a lot to think about and I was left with a complex feeling that the path forward for Italians was not straight.

|

| Vitale Barberis Canonico Swatch Library |

|

| Weaving Machines, Vitale Barberis Canonico |

|

| Michele Papuzzo, head of design at Vitale Barberis Canonico |

|

| A swatch book from the late 1800's |

|

| A roll of finished wool |

|

| Casa Zegna in the hills of Biella |